'Second Space': The Captive Body by Meghan O'Rourke

SECOND SPACE New Poems. By Czeslaw Milosz. Translated by the author and Robert Hass. 102 pp. Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers. $23.95.

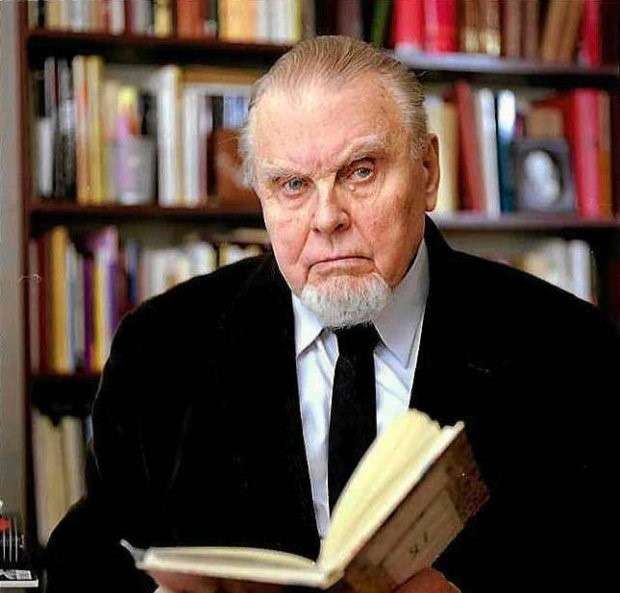

Great honesty comes in two guises: the honesty of the innocent and the honesty of those so haunted by their own dishonesties -- their smallest falsenesses -- that they cannot keep silent about them. The Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz falls into the latter category. Since he died in Krakow on Aug. 14, at the age of 93, numerous tributes have celebrated his remarkable intellectual and artistic integrity, evidenced by his defection in 1951 from Communist Poland -- he was in the diplomatic service at the time, though not a member of the party -- and by his poetry, which never offers a piety when it can dismantle one instead. But Milosz would most likely be made uncomfortable by the praise. "I have always considered myself a crooked tree, so straight trees earned my respect," he tells us in "Milosz's ABC's," his 2001 autobiography-of-sorts.

(Ұлы деуге тұрарлық қарапайымдылық екі түрлі маскада ғана өмір сүріп тұрады: риасыз тазалық пен өзінде айтып жеткізуге болмайтын қасіретті дүниелер бола тұрса да, оны өтірікке айналдырма-ақ, өз әйнінде, өз болмысында, бүркеп-бүкпей-ақ айтып бере алу. Полияк ақыны Czeslaw Milosz осының соңғысына жатады. Осы жылдың 14-тамызында ақын 93 қараған шағында Krakow та өмірден озды. Жұрттың дені оның жұрттан озған ақыл-парасаты мен өнерін ауыз толтыра айтады. Айталық, ол 1951 жылы желі оңынан туып тұрған заманның өзінде өз таңдауын жасаған тұлға. Сол тұста ол дипломат болатын. Ол партияның қатарында болмаса да, жалынды жыр жазудан бас тартқан емес. Оны да қарапайымдылықтың бір парасы деп бағалауға болады. Бірақ, Czeslaw Milosz-тың асыра қызыл мақтау өлең жазуға деген құлқының жоқ болғаны анық. «Мен өзімді қашанда ағаш көрем иілген, / қасқайып тұрған оларды сол үшінде үнатам» деп жазды ол 2001 жылы жарық көрген “Milosz‘s ABC”(Milosz’s ABC‘s) кітабында )

What has earned the respect of Milosz's readers, on the other hand, is the poet's straight talk about that crookedness (or "lameness," the figurative term he preferred). Unlike Robert Lowell, who made the crookedness of the psyche into a Munchian portrait of the ravages of interiority, Milosz demonstrates an interest in the crooked that is social, theological and historical; he meditates on "the basic similarity in humans / And their tiny grain of dissimilarity" rather than the other way round. In "Second Space," his final collection, which has been translated by the author and the poet Robert Hass, he pays even more ruthless attention than usual to everything in him that wavers. "Fickleness -- I had a touch of it," he comments wryly in "Framing." That wryness gives way to graver tones as the book proceeds: "I swore to love you eternally, but later on / my resolution wavered," he writes in "I Should Now," a poem about getting older. We don't necessarily get wiser as we age, Milosz is suggesting; we just get wised-up. Characteristically, the meaning is intensified by his canny diction -- the taut, expressive jolt from the high ("love you eternally") to the low ("but later on").

"Second Space" is in part about the degradations of age; poems testify to the poet's failing eyes ("I am slowly moving away from the fairgrounds of the world") and his exhaustion ("My body doesn't want to take my orders"). But the book is equally about the spiritual degradations of a long life: the resolutions that waver, the attentions that remain unpaid, the relationships that are sacrificed to art; in short, the disparity between the path we hope to walk and the path we walk, and the curious fact that on either path our eyes remain trained on the tutelary warmth of the sun. In writing of the border between life and death, civilization and war, he states: "Everything was fine as long as we were not forced to cross the border. / On this side a nappy green carpet made from the treetops of a tropical forest, we soar over it, we birds."

Milosz, who witnessed Nazism and Stalinism firsthand, long maintained a belief in the redemptive power of art, and for every doubt expressed there is an act of faith to meet it: "In thought some greatness of soul keeps being born," he asserts. But he was equally enchanted by the sensual pleasures of life. In "Orpheus and Eurydice," a brilliant reimagining of the myth, written after the unexpected death of his much younger wife in 2003, Milosz conjures up Orpheus' return to the world:

Sun. And sky. And in the sky white clouds.

Only now everything cried to him: Eurydice!

How will I live without you, my consoling one!

But there was a fragrant scent of herbs, the low humming of bees,

And he fell asleep with his cheek on the sun-warmed earth.

The final sentence is carefully arranged so that the last words are "sun-warmed earth," not "fell asleep" (as a less subtle poet would have chosen); note this, and you begin to grasp the avidity of Milosz's love for the physical world. Note, too, that the luminous final lines describe Orpheus after he has realized that he's lost Eurydice, and you begin to grasp the tragic ironies that inform all of Milosz's mature work.

The "second space" of the title refers to heaven and hell: "Have we really lost faith in that other space? / Have they vanished forever, both Heaven and Hell?" he asks, then enjoins, "Let us implore that it be returned to us / That second space." As a collection, "Second Space," like much of Milosz's work, is a defense of the humanistic values he worries have been lost in an age disillusioned by the Holocaust and awed by enormous technological leaps; in a poem about scientists, he wonders: "What have they left us? / Only the accountancy of a capitalist enterprise."

In "Second Space," Milosz has evolved away from the densely musical verbiage of his earlier years, and is more partial than ever to single lines and couplets. These short stanzas are inherently well suited to non sequiturs, to jumps, to swerves in ratiocination, and much of this last work resounds with interstitial silence, as if the poet were preparing himself for a more enduring quietude:

From human speech to the muteness of verse, how far!

It spreads out, the valley, signs, lights.

The mild valley of those who are eternally alive.

They walk by green waters.

With red ink they draw on my breast

A heart and the signs of a kindly welcome.

Milosz's vaguely archaic language ("a kindly welcome") may have kept some American readers from appreciating the immediacy of his work in the past. Likewise, a strain of dense argumentative poetry makes up a substantial portion of the book, which may not be to all readers' tastes. "Second Space" has five sections, and four consist of a single poem each -- respectively, "Father Severinus" (about a contemporary priest); "Treatise on Theology" (a formulation of Milosz's unorthodox, Swedenborgian Catholicism); the delightful "Apprentice" (a T. S. Eliot-inflected paean to Milosz's uncle, Oscar Milosz, a French-Polish poet and melancholic); and the already mentioned "Orpheus and Eurydice," a poem that ought to take its place among the ranks of Milosz's greatest. The religious poems address the large question that must be answered by any religious person, and perhaps more urgently by one who witnessed the Holocaust: "If God is all-powerful, he can allow all this only if he is not good," Milosz writes.

But the story Milosz is telling is our story, an American one as well as a European one, about broken faith and lost meanings in need of repair. His curiosity about intellectual questions -- and about the endurance of memory -- had that particular quality of persistence that is itself a branch of genius. There are certain human beings who have the capacity to ask the question "Why?" long after everyone else has tired of it (and, perhaps, its attending answer). "Crooked" they may be, like the rest of us -- and yet they set themselves apart by virtue of will. "I should be dead already, but there is work to do," Milosz writes here, in the lovely, fragmented "Notebook." Alas, his work is now in our hands. But our job -- reading it -- is among the most rewarding ones imaginable.

«The New York Times», Nov. 21, 2004

Мақала туралы сілтеме:

https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/21/books/review/second-space-the-captive-body.html