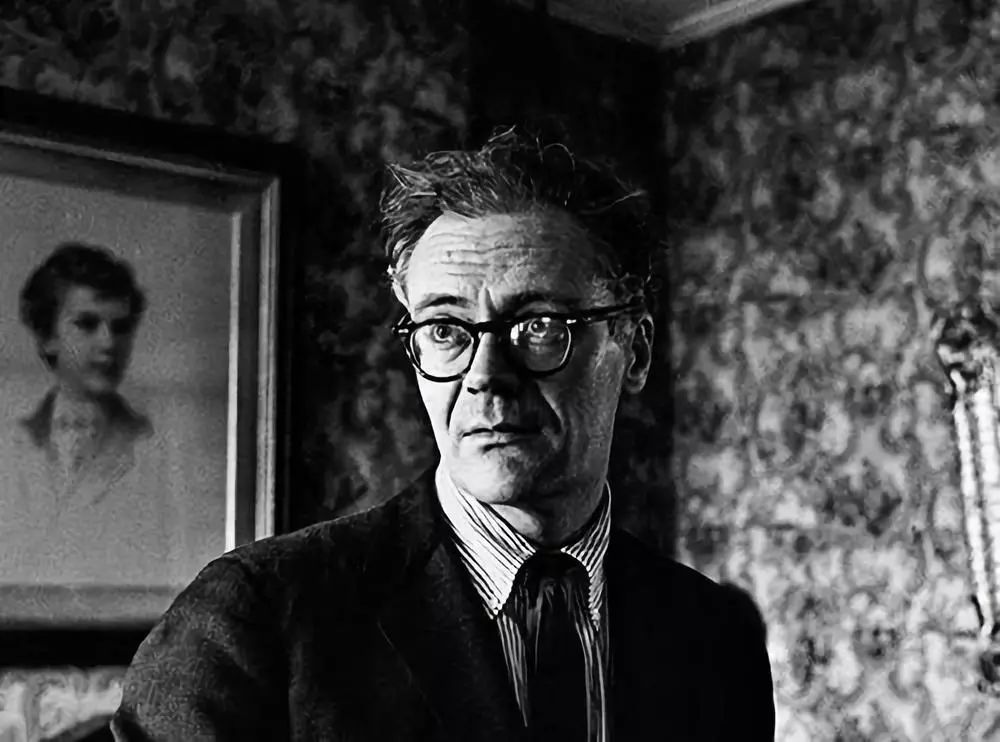

Robert Lowell. For the Union Dead

The old South Boston Aquarium stands

in a Sahara of snow now. Its broken windows are boarded.

The bronze weathervane cod has lost half its scales.

The airy tanks are dry.

Once my nose crawled like a snail on the glass;

my hand tingled

to burst the bubbles,

drifting from the noses of the cowed, compliant fish.

My hand draws back. I often sigh still

for the dark downward and vegetating kingdom

of the fish and reptile. One morning last March,

I pressed against the new barbed and galvanized

fence on the Boston Common. Behind their cage,

yellow dinosaur steam shovels were grunting

as they cropped up tons of mush and grass

to gouge their underworld garage.

Parking lots luxuriate like civic

sand piles in the heart of Boston.

A girdle of orange, Puritan-pumpkin-colored girders

braces the tingling Statehouse,

shaking the excavations, as it faces Colonel Shaw

and his bell-cheeked Negro infantry

on St. Gaudens' shaking Civil War relief,

propped by a plank splint against the garage's earthquake.

Two months after marching through Boston,

half the regiment was dead;

at the dedication,

William James could almost hear the bronze Negroes breathe.

The monument sticks like a fishbone

in the city's throat.

Its colonel is as lean

as a compass needle.

He has an angry wrenlike vigilance,

a greyhound's gentle tautness;

he seems to wince at pleasure

and suffocate for privacy.

He is out of bounds. He rejoices in man's lovely,

peculiar power to choose life and die—

when he leads his black soldiers to death,

he cannot bend his back.

On a thousand small-town New England greens,

the old white churches hold their air

of sparse, sincere rebellion; frayed flags

quilt the graveyards of the Grand Army of the Republic.

The stone statues of the abstract Union Soldier

grow slimmer and younger each year—

wasp-waisted, they doze over muskets,

and muse through their sideburns.

Shaw's father wanted no monument

except the ditch,

where his son's body was thrown

and lost with his "niggers."

The ditch is nearer.

There are no statues for the last war here;

on Boylston Street, a commercial photograph

showed Hiroshima boiling

over a Mosler Safe, "the Rock of Ages,"

that survived the blast. Space is nearer.

When I crouch to my television set,

the drained faces of Negro school children rise like balloons.

Colonel Shaw

is riding on his bubble,

he waits

for the blessed break.

The Aquarium is gone. Everywhere,

giant finned cars nose forward like fish;

a savage servility

slides by on grease.